Listen to a podcast-style discussion of this article or download it here

The Carpenter's Apprentice

Dust motes danced in shafts of morning light that poured through the high windows like a hot knife cutting through butter. Master carpenter Elinor moved with practiced efficiency, her weathered hands transforming rough timber into sturdy, elegant stools, her craftsmanship approximating magic. In the corner, her newest apprentice Thomas hunched over a scroll of parchment, his quill scratching intricate diagrams with jerky unrefined movements.

"Thomas," Elinor called, wiping sweat from her brow, "how are those dovetail joints progressing?"

The young man looked up, eyes bright with enthusiasm like an excited rabbit. "I'm perfecting my technique, Master Elinor! Look at these calculations for the optimal angle." He held up elaborate sketches, arrows and measurements scrawled in precise handwriting.

Elinor nodded patiently. "Very impressive. But the Spring Market is three days away."

"I'll be ready," Thomas promised, returning to his diagrams.

As the days passed, Elinor completed stool after stool—simple, sturdy, functional. Nothing fancy, just honest craftsmanship executed with consistency. Thomas, meanwhile, filled scroll after scroll with increasingly complex designs, constantly revising his "perfect" joinery system.

Market day arrived with the tolling of church bells. Elinor's cart was loaded with two dozen finished stools. Thomas brought his scrolls and a single, half-assembled frame—"to demonstrate the revolutionary design," he explained.

By midday, families crowded Elinor's stall. Children tested the stools with bounces and jumps, mothers approved of their durability, fathers nodded at the fair price and utility. One by one, the stools found new homes.

Thomas stood beside his intricate blueprints, eloquently explaining the superiority of his mathematical approach to anyone who would listen. But as the sun began to set, he watched a young girl skip away, clutching one of Elinor's simple stools, her face beaming with joy.

In that moment, Thomas's expression fell—a mixture of realization and regret washing over his features. His perfect design existed only in theory, while Elinor's "good enough" stools were now scattered throughout the village, serving real people's needs.

Modern portfolios aren't so different from medieval furniture; they're built, not drafted into existence.

The general sentiment has been around for a long time but has been distilled rather elegantly and succinctly by Sheryl Sandberg to convey the idea that highly successful people simply act rather than stewing over ideas.

Done is better than perfect

The Psychology of "Paralysis by Analysis"

"In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is." — Yogi Berra

We've all been Thomas at some point. Standing before a wall of 47 ETFs, comparing expense ratios to the third decimal place. Reading yet another book on asset allocation. Bookmarking our seventeenth investing podcast.

This phenomenon—where excessive thinking impedes action—has a name: analysis paralysis. And it's more costly than we realize.

The psychology behind our hesitation is well-documented. In his seminal work The Paradox of Choice, psychologist Barry Schwartz demonstrates that an abundance of options doesn't liberate us—it paralyzes us. When faced with too many choices (like the dizzying array of index funds), our brains short-circuit. We defer decisions, seek more information, and tell ourselves we're being "thorough" when we're actually procrastinating.

Our hesitation isn't just about complexity—it's emotionally driven. Loss aversion, our tendency to feel the pain of losses more acutely than the pleasure of equivalent gains, makes the prospect of "choosing wrong" feel catastrophic. Better to keep researching than risk regret, we tell ourselves.

Perhaps most insidiously, we've learned that appearing knowledgeable about investing often earns more social credit than quietly building wealth. We signal competence through research and terminology rather than results. This creates a perverse incentive where knowing trivia about expense ratios substitutes for actually investing.

This interplay between the Dunning-Kruger effect (where novices overestimate their abilities) and imposter syndrome (where capable people underestimate themselves) creates a cognitive trap. We either know too little to recognize our limitations or know enough to be paralyzed by them.

The Hidden Cost of Inaction

"The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now." — Chinese Proverb

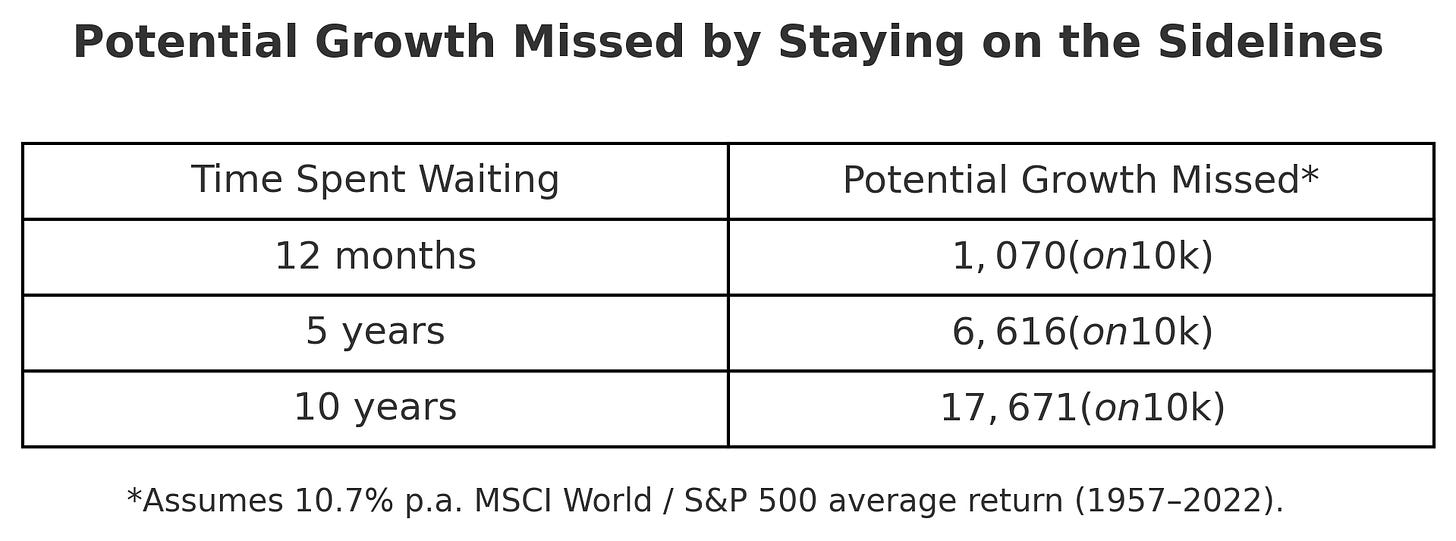

While we endlessly refine our understanding of the "perfect" investment strategy, time—our most precious asset—slips away. Consider this simple opportunity cost calculator:

Time Spent Waiting

Potential Growth Missed (MSCI World Avg)

NB: Uses the widely accepted long-term S&P 500 average annual return of 10.7% (based on historical data from 1957-2022)

These numbers represent more than money—they represent freedom, options, and security permanently foregone. The American Psychological Association's 2024 meta-analysis on decision-making confirms what many of us feel intuitively: rumination and excessive planning correlate with increased stress hormones and reduced self-regulation. Put simply, overthinking doesn't just cost us returns—it costs us wellbeing.

Netflix vs. Nasdaq Consider this: The average American spends 3.1 hours daily on streaming services. Just 15 minutes of that time redirected to setting up automatic investments would generate approximately $140,000 over 30 years (assuming average market returns). I put it to you that approaching retirement with an additional six figures would bring more satisfaction in three decades than having seen every episode of every tv show ever.

Dollar-Cost Averaging: The Anti-Paralysis Protocol

"Complexity is the enemy of execution." — Tony Robbins

Between the sophistication of modern financial engineering and the noise of financial media lies a refreshingly simple truth: consistent, automated investing outperforms most active strategies over time. This insight is formalized as dollar-cost averaging (DCA)—the practice of investing fixed amounts at regular intervals, regardless of market conditions.

The evidence for DCA's effectiveness is overwhelming. Vanguard's 2023 study of investor behaviour found that disciplined DCA investors outperformed market-timing peers by an average of 1.8% annually—not because of superior investment selection, but because of behavioural consistency. Similarly, Fidelity's investor analysis revealed that their most successful individual investors shared one surprising characteristic: many had forgotten they had accounts. Their inattention protected them from panic-selling or overtrading.

DCA works because it aligns with how habits form. According to the habit loop model pioneered by Charles Duhigg, sustainable behaviours require minimal cognitive load. By removing the decision of "when" to invest, DCA reduces the friction that derails most financial plans.

The automation aspect cannot be overstated. When investments occur automatically, they bypass our daily emotional reactions to headlines, market movements, and financial anxieties. The best financial system isn't the most sophisticated—it's the one you'll actually follow.

"The investor's chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself." — Benjamin Graham

Designing Your Minimum-Viable Investing System

"Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication." — Leonardo da Vinci

The most resilient investment systems are remarkably simple, focusing on just three essential levers:

Amount: How much will you invest at regular intervals? (weekly/fortnightly)

Asset: Where will these investments go? (typically a broad-market ETF blend)

Automation Rule: How will this happen without your intervention? (bank transfer + broker auto-invest)

That's it. No complex rebalancing algorithms. No sector rotation strategies. No market timing. Just three decisions that, once made, can run in the background of your life for decades.

Your one-page checklist should cover only:

Risk tolerance assessment (conservative, moderate, or aggressive allocation)

Fee evaluation (under 0.2% for core holdings)

Tax-efficiency consideration (Super/IRA contributions maximized?)

Annual rebalance date (birthday or financial year-end)

Behavioural science offers additional tools to strengthen your commitment. Consider these nudges:

Rename your brokerage account something meaningful like "Future Freedom" or "Kids' Education"

Create accountability by emailing your investment plan to a trusted friend

Set calendar reminders to review (not change) your strategy annually, not daily

"The more complicated the investing process, the less likely it is to be repeated—and repeated behavior is what builds wealth." — Morgan Housel (Author of The Psychology of Money)

Counterarguments & Re-frames

"The stock market is designed to transfer money from the active to the patient." — Warren Buffett

Let's address the three most common objections to simple, automated investing:

"But Timing the Market Feels Smarter" The data contradicts this feeling. J.P. Morgan's analysis of the S&P 500 over 20 years showed that missing just the 10 best days would cut your returns by half. Since these high-return days often follow downturns, attempting to time entries and exits dramatically increases your risk of permanent underperformance.

"I'll Start When Markets Calm Down" What we perceive as "calm" markets are often plateaus before growth. By waiting for "stability," investors typically miss the rapid recoveries that follow volatility. Historical data shows that market timing strategies underperform simple buy-and-hold approaches by 1.2% annually—a difference that compounds to hundreds of thousands over a lifetime.

"What If I Lose My Job?" This valid concern highlights why an emergency fund precedes investing. Your financial foundation should include 3-6 months of expenses in high-yield savings before substantial investing begins. The beauty of DCA is its flexibility—it can be paused without penalty during hardship and resumed when circumstances improve.

Call to (Tiny) Action

"A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step." — Lao Tzu

Theory becomes valuable only when translated into action.

1. Open or log into your brokerage account right now

Set up a $100 (or whatever you can afford) automatic investment for your next pay cycle

Remember: this small action, repeated consistently (and if you automate it it will happen in the background without you doing anything), will outperform 90% of complex investment strategies. The difference between financial security and perpetual worry often comes down to this single decision point.

The Carpenter's Legacy

Ten years after that Spring Market day, Elinor's stools could be found throughout the village—in kitchens, by fireplaces, and under the hands of new apprentices learning their craft. Some showed signs of wear, others had been lovingly repaired, but all served their purpose faithfully.

Thomas had become something of a local wood-philosopher, still discussing the theoretical perfection of joinery techniques. His diagrams were admired for their precision and artistry. Yet in his own home, when he needed a place to sit, he used a stool he had purchased—from Elinor.

"Knowledge unused is the same as ignorance."

The financial markets, like woodworking, reward the doers. Those who build—even imperfectly—create something that simply cannot emerge from pure theory, no matter how elegant.

Start building today.

Warmly, Ryan

The behavioral side of investing and the reducation of the cognitive load is one of the reasons I think robo-advisors are such a good choice for many investors 😊